Background

The relational model, developed as a result of recognized shortcomings

of hierarchical and network DBMSs, was introduced by Codd in 1970. As

the major developer, Codd believed that a sound theoretical model would

solve many practical problems that might arise.

In another article, Codd expounds the case for adopting the relational

over earlier database models. There is a threefold thrust to his

argument. First, earlier models forced the programmer to code at a

low level of structural detail. As a result, application programs are

more complex and took longer to write and debug. Second, no commands

were provided for processing multiple records at one time. Earlier models

did not provide the set-processing capability of the relational model.

The set-processing feature means that queries can be more concisely

expressed. Third, the relational model, through a query language such

as structured query language (SQL), recognizes the clients’ need to make

ad hoc queries. The relational model and SQL permit an IS department to

respond rapidly to unanticipated requests. It also meant that

analysts could write queries. Thus, Codd’s assertion that the

relational model is a practical tool for increasing the productivity of

IS departments is well founded.

The productivity increase arises from three of the objectives that drove

Codd’s research. The first was to provide a clearly delineated

boundary between the logical and physical aspects of database

management. Programming should be divorced from considerations of the

physical representation of data. Codd labels this the data

independence objective. The second objective was to create a simple

model that is readily understood by a wide range of analysts and

programmers. This communicability objective promotes effective and

efficient communication between clients and IS personnel. The third

objective was to increase processing capabilities from record-at-a-time

to multiple-records-at-a-time—the set-processing objective.

Achievement of these objectives means fewer lines of code are required

to write an application program, and there is less ambiguity in

client-analyst communication.

The relational model has three major components:

Data structures

Like most theories, the relational model is based on some key structures

or concepts. We need to understand these in order to understand the

theory.

Domain

A domain is a set of values all of the same data type. For example, the

domain of nation name is the set of all possible nation names. The

domain of all stock prices is the set of all currency values in, say,

the range $0 to $10,000,000. You can think of a domain as all the

legal values of an attribute.

In specifying a domain, you need to think about the smallest unit of

data for an attribute defined on that domain. In Chapter 8, we discussed

how a candidate attribute should be examined to see whether it should be

segmented (e.g., we divide name into first name, other name, and last

name, and maybe more). While it is unlikely that name will be a domain,

it is likely that there will be a domain for first name, last name, and

so on. Thus, a domain contains values that are in their atomic state;

they cannot be decomposed further.

The practical value of a domain is to define what comparisons are

permissible. Only attributes drawn from the same domain should be

compared; otherwise it is a bit like comparing bananas and strawberries.

For example, it makes no sense to compare a stock’s PE ratio to its

price. They do not measure the same thing; they belong to different

domains. Although the domain concept is useful, it is rarely supported

by relational model implementations.

Relations

A relation is a table of n columns (or attributes) and m rows (or

tuples). Each column has a unique name, and all the values in a column

are drawn from the same domain. Each row of the relation is uniquely

identified. The order of columns and rows is immaterial.

The cardinality of a relation is its number of rows. The degree

of a relation is the number of columns. For example, the relation nation

(see the following figure) is of degree 3 and has a cardinality of 4.

Because the cardinality of a relation changes every time a row is added

or deleted, you can expect cardinality to change frequently. The degree

changes if a column is added to a relation, but in terms of relational

theory, it is considered to be a new relation. So, only a relation’s

cardinality can change.

A relational database with tables nation and stock

| AUS |

Australia |

0.46 |

| IND |

India |

0.0228 |

| UK |

United Kingdom |

1 |

| USA |

United States |

0.67 |

| FC |

Freedonia Copper |

27.5 |

10,529 |

1.84 |

16 |

UK |

| PT |

Patagonian Tea |

55.25 |

12,635 |

2.5 |

10 |

UK |

| AR |

Abyssinian Ruby |

31.82 |

22,010 |

1.32 |

13 |

UK |

| SLG |

Sri Lankan Gold |

50.37 |

32,868 |

2.68 |

16 |

UK |

| ILZ |

Indian Lead & Zinc |

37.75 |

6,390 |

3 |

12 |

UK |

| BE |

Burmese Elephant |

0.07 |

154,713 |

0.01 |

3 |

UK |

| BS |

Bolivian Sheep |

12.75 |

231,678 |

1.78 |

11 |

UK |

| NG |

Nigerian Geese |

35 |

12,323 |

1.68 |

10 |

UK |

| CS |

Canadian Sugar |

52.78 |

4,716 |

2.5 |

15 |

UK |

| ROF |

Royal Ostrich Farms |

33.75 |

1,234,923 |

3 |

6 |

UK |

| MG |

Minnesota Gold |

53.87 |

816,122 |

1 |

25 |

USA |

| GP |

Georgia Peach |

2.35 |

387,333 |

0.2 |

5 |

USA |

| NE |

Narembeen Emu |

12.34 |

45,619 |

1 |

8 |

AUS |

| QD |

Queensland Diamond |

6.73 |

89,251 |

0.5 |

7 |

AUS |

| IR |

Indooroopilly Ruby |

15.92 |

56,147 |

0.5 |

20 |

AUS |

| BD |

Bombay Duck |

25.55 |

167,382 |

1 |

12 |

IN |

Relational database

A relational database is a collection of relations or tables. A

distinguishing feature of the relational model, is that there are no explicit linkages between tables. Tables are linked by common columns drawn on the same

domain; thus, the portfolio database (see the preceding tables) consists

of tables stock and nation. The 1:m relationship between the two

tables is represented by the column natcode that is common to both

tables. Note that the two columns need not have the same name, but they

must be drawn on the same domain so that comparison is possible. In the

case of an m:m relationship, while a new table must be created to

represent the relationship, the principle of linking tables through

common columns on the same domain remains in force.

Primary key

A relation’s primary key is its unique identifier; for example, the

primary key of nation is natcode. As you already know, a primary key

can be a composite of several columns. The primary key guarantees that

each row of a relation can be uniquely addressed.

Candidate key

In some situations, there may be several attributes, known as candidate

keys, that are potential primary keys. Column natcode is unique in the

nation relation, for example. We also can be fairly certain that two

nations will not have the same name. Therefore, nation has multiple

candidate keys: natcode and natname.

Alternate key

When there are multiple candidate keys, one is chosen as the primary

key, and the remainder are known as alternate keys. In this case, we

selected natcode as the primary key, and natname is an alternate

key.

Foreign key

The foreign key is an important concept of the relational model. It is

the way relationships are represented and can be thought of as the glue

that holds a set of tables together to form a relational database. A

foreign key is an attribute (possibly composite) of a relation that is

also a primary key of a relation. The foreign key and primary key may be

in different relations or the same relation, but both keys must be drawn

from the same domain.

Integrity rules

The integrity section of the relational model consists of two rules. The

entity integrity rule ensures that each instance of an entity

described by a relation is identifiable in some way. Its implementation

means that each row in a relation can be uniquely distinguished. The

rule is

No component of the primary key of a relation may be null.

Null in this case means that the component cannot be undefined or

unknown; it must have a value. Notice that the rule says “component of a

primary key.” This means every part of the primary key must be known. If

a portion of the key cannot be defined, it implies that the particular entity it

describes cannot be defined. In practical terms, it means you cannot add

a nation to nation unless you also define a value for natcode.

The definition of a foreign key implies that there is a corresponding

primary key. The referential integrity rule ensures that this is the

case. It states

A database must not contain any unmatched foreign key values.

Simply, this rule means that you cannot define a foreign key without

first defining its matching primary key. In practical terms, it would

mean you could not add a Canadian stock to the stock relation without

first creating a row in nation for Canada.

Notice that the concepts of foreign key and referential integrity are

intertwined. There is not much sense in having foreign keys without

having the referential integrity rule. Permitting a foreign key without

a corresponding primary key means the relationship cannot be determined.

Note that the referential integrity rule does not imply a foreign key

cannot be null. There can be circumstances where a relationship does not

exist for a particular instance, in which case the foreign key is null.

Manipulation languages

There are four approaches to manipulating relational tables, and you are

already familiar with SQL, the major method.

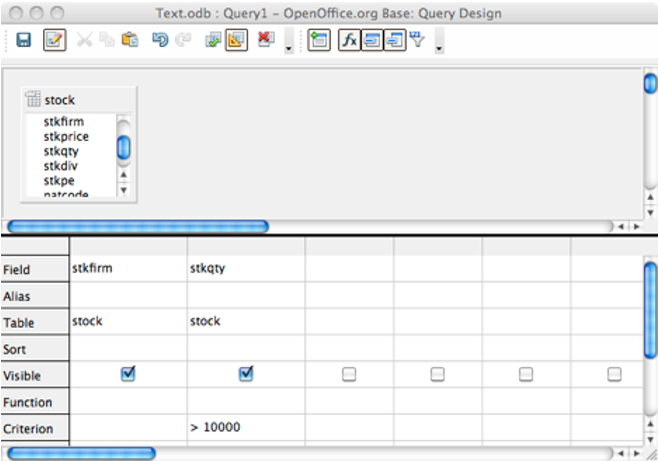

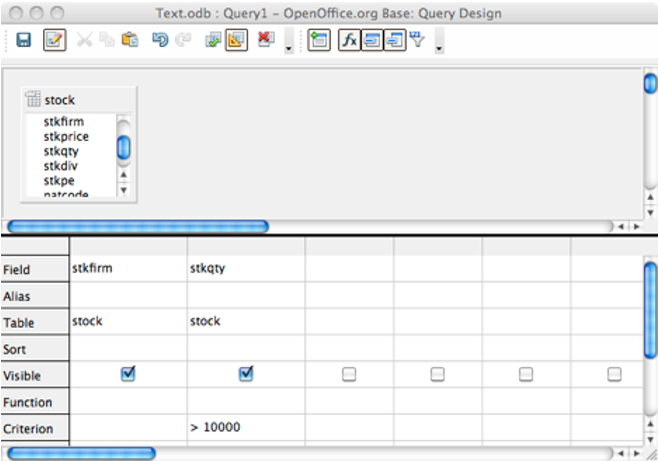

Query-by-example (QBE), which describes a

general class of graphical interfaces to a relational database to make

it easier to write queries, is also commonly used. Less widely used

manipulation languages are relational algebra and relational calculus.

These languages are briefly discussed, with some attention given to

relational algebra in the next section and SQL in the following chapter.

Query-by-example (QBE) is not a standard, and each vendor implements

the idea differently. The general principle is to enable those with

limited SQL skills to interrogate a relational database. Thus, the

analyst might select tables and columns using drag and drop or by

clicking a button. The following screen shot shows the QBE interface to

LibreOffice, which is very similar to that of MS Access. It shows

selection of the stock table and two of its columns, as well as a

criterion for stkqty. QBE commands are translated to SQL prior to

execution, and many systems allow you to view the generated SQL. This

can be handy. You can use QBE to generate a portion of the SQL for a

complex query and then edit the generated code to fine-tune the query.

Query-by-example with LibreOffice

Relational algebra has a set of operations similar to traditional

algebra (e.g., add and multiply) for manipulating tables. Although

relational algebra can be used to resolve queries, it is seldom

employed, because it requires you to specify both what you want and how

to get it. That is, you have to specify the operations on each table.

This makes relational algebra more difficult to use than SQL, where the

focus is on specifying what is wanted.

Relational calculus overcomes some of the shortcomings of relational

algebra by concentrating on what is required. In other words, there is

less need to specify how the query will operate. Relational calculus is

classified as a nonprocedural language, because you do not have to be

overly concerned with the procedures by which a result is determined.

Unfortunately, relational calculus can be difficult to learn, and as a

result, language designers developed SQL and QBE, which are

nonprocedural and more readily mastered. You have already gained some

skills in SQL. Although QBE is generally easier to use than SQL, IS

professionals need to master SQL for two reasons. First, SQL is

frequently embedded in other programming languages, a feature not

available with QBE. Second, it is very difficult, or impossible, to

express some queries in QBE (e.g., divide). Because SQL is important, it

is the focus of the next chapter.

Relational algebra

The relational model includes a set of operations, known as relational

algebra, for manipulating relations. Relational algebra is a standard

for judging data retrieval languages. If a retrieval language, such as

SQL, can be used to express every relational algebra operator, it is

said to be relationally complete.

Relational algebra operators

| Restrict |

Creates a new table from specified rows of an existing table |

| Project |

Creates a new table from specified columns of an existing table |

| Product |

Creates a new table from all the possible combinations of rows of two existing tables |

| Union |

Creates a new table containing rows appearing in one or both tables of two existing tables |

| Intersect |

Creates a new table containing rows appearing in both tables of two existing tables |

| Difference |

Creates a new table containing rows appearing in one table but not in the other of two existing tables |

| Join |

Creates a new table containing all possible combinations of rows of two existing tables satisfying the join condition |

| Divide |

Creates a new table containing xi such that the pair (xi, yi) exists in the first table for every yi in the second table |

There are eight relational algebra operations that can be used with

either one or two relations to create a new relation. The assignment

operator (:=) indicates the name of the new relation. The relational

algebra statement to create relation A, the union of relations B and C,

is expressed as

A := B UNION C

Before we begin our discussion of each of the eight operators, note that

the first two, restrict and project, operate on a single relation and

the rest require two relations.

Restrict

Restrict extracts specified rows from a single relation. It takes a horizontal slice through a relation.

Project

Project extracts specified columns from a table. It takes a vertical slice through a table.

Product

Product creates a new relation from all possible combinations of rows in

two other relations. It is sometimes called TIMES or MULTIPLY. The

relational command to create the product of two tables is

The operation of product is illustrated in the following figure, which

shows the result of A TIMES B.

Relational operator product

| V |

W |

|

X |

Y |

Z |

| v1 |

w1 |

|

x1 |

y1 |

z1 |

| v2 |

w2 |

|

x2 |

y2 |

z2 |

| v3 |

w3 |

|

|

|

|

A TIMES B

| v1 |

w1 |

x1 |

y1 |

z1 |

| v1 |

w1 |

x2 |

y2 |

z2 |

| v2 |

w2 |

x1 |

y1 |

z1 |

| v2 |

w2 |

x2 |

y2 |

z2 |

| v3 |

w3 |

x1 |

y1 |

z1 |

| v3 |

w3 |

x2 |

y2 |

z2 |

Union

The union of two relations is a new relation containing all rows

appearing in one or both relations. The two relations must be union

compatible, which means they have the same column names, in the same

order, and drawn on the same domains. Duplicate rows are automatically

eliminated—they must be, or the relational model is no longer

satisfied. The relational command to create the union of two tables is

Union is illustrated in the following figure. Notice that corresponding

columns in tables A and B have the same names. While the sum of the

number of rows in relations A and B is five, the union contains four

rows, because one row (x2, y2 ) is common to both relations.

Relational operator union

| X |

Y |

|

X |

Y |

| x1 |

y1 |

|

x2 |

y2 |

| x2 |

y2 |

|

x4 |

y4 |

| x3 |

y3 |

|

|

|

A UNION B

Intersect

The intersection of two relations is a new relation containing all rows

appearing in both relations. The two relations must be union compatible.

The relational command to create the intersection of two tables is

The result of A INTERSECT B is one row, because only one row (x2,

y2) is common to both relations A and B.

Relational operator intersect

| X |

Y |

|

X |

Y |

| x1 |

y1 |

|

x2 |

y2 |

| x2 |

y2 |

|

x4 |

y4 |

| x3 |

y3 |

|

|

|

A INTERSECT B

Difference

The difference between two relations is a new relation containing all

rows appearing in the first relation but not in the second. The two

relations must be union compatible. The relational command to

create the difference between two tables is

The result of A MINUS B is two rows (see the following figure). Both of

these rows are in relation A but not in relation B. The row containing

(x1, y2) appears in both A and B and thus is not in A MINUS B.

Relational operator difference

| X |

Y |

|

X |

Y |

| x1 |

y1 |

|

x2 |

y2 |

| x2 |

y2 |

|

x4 |

y4 |

| x3 |

y3 |

|

|

|

A MINUS B

Join

Join creates a new relation from two relations for all combinations of

rows satisfying the join condition. The general format of join is

where theta can be =, <>, >, >=, <, or <=.

The following figure illustrates A JOIN B WHERE W = Z, which is an

equijoin because theta is an equals sign. Tables A and B are matched

when values in columns W and Z in each relation are equal. The matching

columns should be drawn from the same domain. You can also think of join

as a product followed by restrict on the resulting relation.

Relational operator join

| V |

W |

|

X |

Y |

Z |

| v1 |

wz1 |

|

x1 |

y1 |

wz1 |

| v2 |

wz2 |

|

x2 |

y2 |

wz2 |

| v3 |

wz3 |

|

|

|

|

A EQUIJOIN B

| v1 |

wz1 |

x1 |

y1 |

wz1 |

| v3 |

wz3 |

x2 |

y2 |

wz3 |

Divide

Divide is the hardest relational operator to understand. Divide requires

that A and B have a set of attributes, in this case Y, that are common

to both relations. Conceptually, A divided by B asks the question, “Is

there a value in the X column of A (e.g., x1) that has a value in the

Y column of A for every value of y in the Y column of B?” Look first at

B, where the Y column has values y1 and y2. When you examine the X

column of A, you find there are rows (x1, y1) and (x1, y2). That

is, for x1, there is a value in the Y column of A for every value of y

in the Y column of B. Thus, the result of the division is a new relation

with a single row and column containing the value x1.

Relational operator divide

| X |

Y |

|

Y |

| x1 |

y1 |

|

y1 |

| x1 |

y3 |

|

y2 |

| x1 |

y2 |

|

|

| x2 |

y1 |

|

|

| x3 |

y3 |

|

|

A DIVIDE B

A primitive set of relational operators

The full set of eight relational operators is not required. As you have

already seen, join can be defined in terms of product and restrict.

Intersection and divide can also be defined in terms of other commands.

Indeed, only five operators are required: restrict, project, product,

union, and difference. These five are known as primitives because

these are the minimal set of relational operators. None of the primitive

operators can be defined in terms of the other operators.

A fully relational database

The three components of a relational database system are structures

(domains and relations), integrity rules (primary and foreign keys), and

a manipulation language (relational algebra). A fully relational

database system provides complete support for each of these

components. Many commercial systems support SQL but do not provide

support for domains. Such systems are not fully relational but are

relationally complete.

In 1985, Codd established the 12 commandments of relational database

systems (see the following table). In addition to providing some

insights into Codd’s thinking about the management of data, these rules

can also be used to judge how well a database fits the relational model.

The major impetus for these rules was uncertainty in the marketplace

about the meaning of “relational DBMS.” Codd’s rules are a checklist for

establishing the completeness of a relational DBMS. They also provide a

short summary of the major features of the relational DBMS.

Codd’s rules for a relational DBMS

| The information rule |

| The guaranteed access rule |

| Systematic treatment of null values |

| Active online catalog of the relational model |

| The comprehensive data sublanguage rule |

| The view updating rule |

| High-level insert, update, and delete |

| Physical data independence |

| Logical data independence |

| Integrity independence |

| Distribution independence |

| The nonsubversion rule |

The guaranteed access rule

Every value in a database must be addressable by specifying its table

name, column name, and the primary key of the row in which it is stored.

Systematic treatment of null values

There must be a distinct representation for unknown or inappropriate

data. This must be unique and independent of data type. The DBMS should

handle null data in a systematic way. For example, a zero or a blank

cannot be used to represent a null. This is one of the more troublesome

areas because null can have several meanings (e.g., missing or

inappropriate).

Active online catalog of the relational model

There should be an online catalog that describes the relational model.

Authorized users should be able to access this catalog using the DBMS’s

query language (e.g., SQL).

The comprehensive data sublanguage rule

There must be a relational language that supports data definition, data

manipulation, security and integrity constraints, and transaction

processing operations. Furthermore, this language must support both

interactive querying and application programming and be expressible in

text format. SQL fits these requirements.

The view updating rule

The DBMS must be able to update any view that is theoretically

updatable.

High-level insert, update, and delete

The system must support set-at-a-time operations. For example, multiple

rows must be updatable with a single command.

Physical data independence

Changes to storage representation or access methods will not affect

application programs. For example, application programs should remain

unimpaired even if a database is moved to a different storage device or

an index is created for a table.

Logical data independence

Information-preserving changes to base tables will not affect

application programs. For instance, no applications should be affected

when a new table is added to a database.

Integrity independence

Integrity constraints should be part of a database’s definition rather

than embedded within application programs. It must be possible to change

these constraints without affecting any existing application programs.

Distribution independence

Introduction of a distributed DBMS or redistribution of existing

distributed data should have no impact on existing applications.

The nonsubversion rule

It must not be possible to use a record-at-a-time interface to subvert

security or integrity constraints. You should not be able, for example,

to write a Java program with embedded SQL commands to bypass security

features.

Codd issued an additional higher-level rule, rule 0, which states that a

relational DBMS must be able to manage databases entirely through its

relational capacities. In other words, a DBMS is either totally

relational or it is not relational.

Summary

The relational model developed as a result of recognized shortcomings of

hierarchical and network DBMSs. Codd created a strong theoretical base

for the relational model. Three objectives drove relational database

research: data independence, communicability, and set processing. The

relational model has domain structures, integrity rules, and operators

used to retrieve, derive, or modify data. A domain is a set of values

all of the same data type. The practical value of a domain is to define

what comparisons are permissible. A relation is a table of n columns

and m rows. The cardinality of a relation is its number of rows. The

degree of a relation is the number of columns.

A relational database is a collection of relations. The distinguishing

feature of the relational model is that there are no explicit linkages

between tables. A relation’s primary key is its unique identifier. When

there are multiple candidates for the primary key, one is chosen as the

primary key and the remainder are known as alternate keys. The foreign

key is the way relationships are represented and can be thought of as

the glue that binds a set of tables together to form a relational

database. The purpose of the entity integrity rule is to ensure that

each entity described by a relation is identifiable in some way. The

referential integrity rule ensures that you cannot define a foreign key

without first defining its matching primary key.

The relational model includes a set of operations, known as relational

algebra, for manipulating relations. There are eight operations that can

be used with either one or two relations to create a new relation. These

operations are restrict, project, product, union, intersect, difference,

join, and divide. Only five operators, known as primitives, are required

to define all eight relational operations. An SQL statement can be

translated to relational algebra and vice versa. If a retrieval language

can be used to express every relational algebra operator, it is said to

be relationally complete. A fully relational database system provides

complete support for domains, integrity rules, and a manipulation

language. Codd set forth 12 rules that can be used to judge how well a

database fits the relational model. He also added rule 0—a DBMS is

either totally relational or it is not relational.

Key terms and concepts

| Alternate key |

Join |

| Candidate key |

Logical data independence |

| Cardinality |

Nonsubversion rule |

| Catalog |

Null |

| Communicability objective |

Operators |

| Data independence |

Physical data independence |

| Data structures |

Primary key |

| Data sublanguage rule |

Product |

| Degree |

Project |

| Difference |

Query-by-example (QBE) |

| Distribution independence |

Referential integrity |

| Divide |

Relational algebra |

| Domain |

Relational calculus |

| Entity integrity |

Set processing objective |

| Foreign key |

Relational database |

| Fully relational database |

Relational model |

| Guaranteed access rule |

Relationally complete |

| Information rule |

Relations |

| Integrity independence |

Restrict |

| Integrity rules |

Union |

| Intersect |

View updating rule |

References and additional readings

Codd, E. F. 1982. Relational database: A practical foundation for

productivity. Communications of the ACM 25 (2):109–117.